Diagnosing and staging feline chronic kidney disease

Rosanne Jepson BVSc (Dist) MVetMed PhD DipACVIM MRCVS - 16/05/2014

Diagnosing and staging feline kidney disease

Rosanne Jepson BVSc (Dist) MVetMed PhD DipACVIM MRCVS

Cats with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are seen every week in veterinary practices across the country. Over the next few years this case load is only likely to increase due to the ageing cat population. To continue this special focus on chronic disease in cats, Rosanne Jepson from the Royal Veterinary College reviews the diagnosis and staging of CKD in cats.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a commonly recognised condition that particularly affects the geriatric (>9 years) feline population. It is important to have a thorough understanding of how to diagnose CKD so that an early diagnosis can be made and appropriate treatment offered. Recently a staging scheme has been introduced by the International Renal Interest Society (IRIS), which can help in monitoring and managing cats diagnosed with CKD.1

Damage that occurs to the kidney is irreversible. Although the kidney can respond to damage, these mechanisms are often ultimately detrimental, and therefore CKD should be considered an intrinsically progressive disease. Some cats diagnosed with CKD will have stable disease for many years, but others will progress rapidly towards end stage disease. Understanding the factors associated with disease progression can help us provide optimal treatment recommendations in order to maintain renal function and slow disease progression.

From human medicine and experimental studies, factors associated with progression of CKD include proteinuria, hypertension, anaemia, chronic hypoxia, ischaemia, oxidative stress, activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, hyperphosphataemia and renal secondary hyperparathyroidism. Some of these factors, including hyperphosphataemia, proteinuria and haematocrit or packed cell volume, are common to studies that have looked at survival of cats with CKD.2,3

It is widely reported that 75% of functioning nephrons can be lost before it is possible to detect azotaemia on a routine biochemistry profile. With this in mind, by the time a clinical diagnosis of CKD is made, the changes present in the kidney are already advanced. Early clinical diagnosis offers the best chance of starting treatment and management strategies that can minimise further kidney damage and slow progression of this disease.

Diagnosing chronic kidney disease

Feline CKD should be diagnosed by obtaining a careful history, performing a thorough physical examination and by evaluating kidney function. Some cats diagnosed at an early time point in the course of their disease will be completely asymptomatic. In this situation CKD may only be detected if a thorough physical examination and screening of kidney function is performed. Routine screening is widely recommended for geriatric cats over the age of 8-9 years on an annual basis.

In any cat with suspected CKD a minimum diagnostic database should be performed (Table 1). Kidney function should always be assessed before starting fluid therapy. Azotaemia is the biochemical finding of increased urea and creatinine concentrations in the blood and should not be confused with uraemia. Uraemia is the clinical syndrome seen in patients with severe azotaemia and includes clinical signs such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, halitosis, oral ulceration, stomatitis, melaena, weakness, muscular tremors and altered mentation. The biochemistry profile should also be used to identify other abnormalities commonly associated with CKD including hypokalaemia, hyperphosphataemia, hypercholesterolaemia and total hyper- or hypocalcaemia.

Assessment of azotaemia on a biochemistry profile should always be performed in combination with a urinalysis. Increased creatinine concentration alone is not diagnostic for CKD. Measurement of urine specific gravity (USG) is required to give an indication of urine concentrating ability. The presence of azotaemia by itself cannot differentiate between pre-renal, renal and post-renal causes.

- Pre-renal azotaemia is caused by a reduction in perfusion to the kidney, e.g. during dehydration, hypovolaemia or hypotension and if kidney function is normal will be associated with well concentrated urine. For the cat this means a USG >1.035 and often considerably higher.

- Renal azotaemia occurs when there has been loss of functioning nephrons and a decrease in intrinsic kidney function. Urine concentration is usually inadequate (USG <1.035)

- Post-renal azotaemia results from either obstruction to the urinary tract (e.g. ureteral or urethral obstruction) or from urine leakage (e.g. uroabdomen).

Assessing glomerular filtration rate

The gold standard for assessing kidney function is to directly measure glomerular filtration rate (GFR). This is rarely performed in clinical practice and instead urea and creatinine are used as markers of GFR. Urea and creatinine have an exponential relationship with GFR (Figure 1), which means they are insensitive in the very early stages of CKD. There are a number of other limitations to using urea and creatinine as markers of GFR.

Urea is synthesised in the liver from ammonia. It is freely filtered at the glomerulus but absorption can occur in the tubules. There are a number of situations where urea may be falsely increased or decreased

False increase:

- During hypovolaemia or dehydration when the degree of tubular reabsorption is increased

- Recent feeding

- Gastrointestinal haemorrhage

False decrease:

- Catabolic state (starvation, anorexia, cachexia)

- Feeding a low protein diet

- Reduced hepatic function

Creatinine is a non-enzymatic breakdown product of phosphocreatine from muscle. It is freely filtered at the glomerulus and is not reabsorbed in the tubules. As creatinine production is dependent on body muscle, poor muscle condition can falsely decrease creatinine concentrations.

This is of particular concern in the geriatric cat with muscle wastage

This is of particular concern in the geriatric cat with muscle wastage

In addition, it is important to consider whether any other disease conditions could be influencing GFR, for example hyperthyroidism where GFR is falsely increased and can mask underlying CKD.

At point A where GFR is normal, any insult to the kidney resulting in a decrease in GFR will result in only a very small change in creatinine concentration. At point B where GFR is low, any further decrease in GFR is mirrored by a much more marked and easily detectable change in creatinine concentration.

Figure 1: Graph demonstrating the exponential relationship between GFR and creatinine concentration.

Performing a urinalysis

Urinalysis is an easy and vital part of assessing kidney function but is  often overlooked. Urine should be obtained before any fluid therapy is given and can be collected by free catch using non absorbent material in a litter tray, cystocentesis or, less often, by catheterisation. It is important to consider the method of collection when interpreting urinalysis results. Cystocentesis is an easy procedure to perform in the cat. It is usually well-tolerated conscious, either with the cat standing or in lateral recumbency (Figure 2) and is the preferred method of collection for urine culture.

often overlooked. Urine should be obtained before any fluid therapy is given and can be collected by free catch using non absorbent material in a litter tray, cystocentesis or, less often, by catheterisation. It is important to consider the method of collection when interpreting urinalysis results. Cystocentesis is an easy procedure to perform in the cat. It is usually well-tolerated conscious, either with the cat standing or in lateral recumbency (Figure 2) and is the preferred method of collection for urine culture.

Figure 2. Photograph of a cat standing for cystocentesis to be performed.

A full urinalysis should always include:

- Gross assessment of urine appearance

- Measurement of specific gravity using a refractometer

- Dipstick assessment of pH, proteinuria, glycosuria, blood, haemoglobin, bilirubinuria

- Sediment examination for cells (epithelial, red and white blood cells), bacteria, casts, crystals, lipid droplets

- Urine culture

- Urine protein to creatinine ratio

About 20% of cats diagnosed with CKD will have a urinary tract infection (UTI). Urine culture should always be performed if there is evidence of an active sediment, pyuria or bactiuria, on microscopic examination. However, occult UTIs are common and many cats with CKD will not show clinical signs of cystitis. Routine urine culture is therefore recommended at diagnosis of CKD.

Proteinuria

Renal proteinuria has been identified as a risk factor associated with the development of azotaemia in geriatric cats and with survival of cats diagnosed with CKD.2,4 Proteinuria can be pre-renal (e.g. Bence-Jones proteins), renal or post-renal (associated with inflammation of the urinary tract). Microscopic haematuria alone may not greatly influence assessment of proteinuria. However, gross haematuria and pyuria can impact on measurement, and it is therefore recommended to identify these changes and to treat any underlying UTI or inflammation prior to assessing proteinuria.

Traditionally, proteinuria is assessed using a urine dipstick. Although this is a good screening test, both false positive and negative results can occur.5 Dipstick tests for protein should be interpreted in light of the USG. For example, 2+ proteinuria is more likely to be of significance with a USG of 1.012 than with a USG of 1.050. Measurement of urine protein to creatinine ratio (UP/C) provides a quantitative assessment of proteinuria.5 Healthy cats typically have a UP/C <0.2 and even in cats with CKD, UP/C usually remains <0.4. This reflects the fact that CKD in cats is primarily a disorder affecting the tubules rather than the glomeruli. Nevertheless, even this low level proteinuria may be important and assessment of UP/C should be considered part of a minimum diagnostic database when evaluating cats with CKD.6

Diagnosis and IRIS staging

A diagnosis of CKD is usually made by documenting azotaemia with inappropriate urine concentrating ability. Ideally, persistence of these findings is confirmed by repeating assessment of kidney function after a period of 2-4 weeks. This repeat assessment also helps to establish how quickly the disease is progressing.

The International Renal Interest Society (IRIS), an international group of key opinion holders in the sphere of veterinary nephrology and urology, has developed guidelines for the staging of feline CKD. Staging is particularly useful for describing severity of disease, considering appropriate treatment and management strategies and advising on prognosis.1

The IRIS staging scheme should only be used after a diagnosis of CKD has been made. The IRIS

staging scheme classifies cats with CKD according to their creatinine concentration (Table 2). Ideally, staging is performed using 2 creatinine concentrations performed several weeks apart indicating stable disease. The cat should be fasted and any pre-renal azotaemia corrected prior to staging of CKD.

staging scheme classifies cats with CKD according to their creatinine concentration (Table 2). Ideally, staging is performed using 2 creatinine concentrations performed several weeks apart indicating stable disease. The cat should be fasted and any pre-renal azotaemia corrected prior to staging of CKD.

Creatinine concentration is staged from 1 to 4. Cats in the later half of stage 2, stage 3 and 4 will be azotaemic. However, cats in stage 1 and the first half of stage 2 will be non-azotaemic. This provides the flexibility to recognise that a large amount of damage can occur in the kidney before azotaemia is detected. Situations when cats may be classified as IRIS stage 1 or early stage 2 CKD include:

- Persistently poor urine concentrating ability

- Persistent non-azotaemic proteinuria (e.g. membranous nephropathy)

- Abnormalities detected on renal palpation and diagnostic imaging

- Knowledge of previous nephrotoxic insult

- Evidence of nephrolithiasis

- Abnormalities detected on renal biopsy

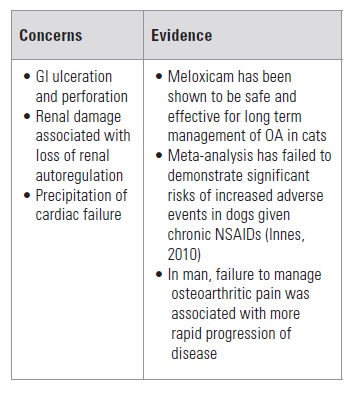

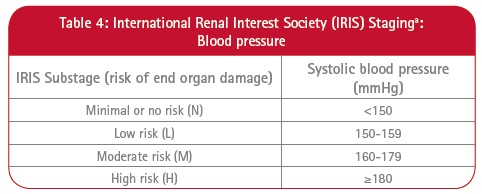

Having staged for creatinine concentration, IRIS provides substaging for both proteinuria (Table 3) and blood pressure (Table 4). IRIS also provides treatment guidelines which aim to prevent further damage to the kidney and to slow disease progression. Some general treatment recommendations are common to all IRIS stages, for example avoiding and if possible discontinuing any nephrotoxic medications, preventing or treating dehydration and hypovolaemia, treating UTIs and maintaining adequate nutrition.

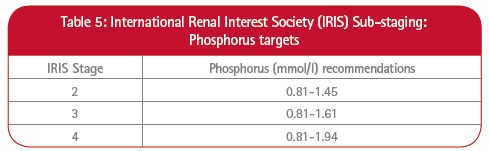

The cornerstone of treatment of CKD is control of hyperphosphataemia and renal secondary hyperparathyroidism. Studies have shown that survival is improved in cats with CKD that are fed a phosphate restricted kidney diet.7,8 IRIS recommends a phosphate restricted kidney diet for all cats with IRIS stage 2-4 CKD. Phosphate restriction is recommended even if initial phosphate concentrations are within reference interval because previous studies have shown that these cats can still have increased parathyroid hormone concentrations. IRIS provides targets for ideal phosphorus concentrations for each stage of CKD (Table 5). Although it is usually possible to achieve the targets with a kidney diet alone in IRIS stage 2 CKD, by IRIS stage 3 and 4 oral phosphate binders may be needed in addition to diet.

The cornerstone of treatment of CKD is control of hyperphosphataemia and renal secondary hyperparathyroidism. Studies have shown that survival is improved in cats with CKD that are fed a phosphate restricted kidney diet.7,8 IRIS recommends a phosphate restricted kidney diet for all cats with IRIS stage 2-4 CKD. Phosphate restriction is recommended even if initial phosphate concentrations are within reference interval because previous studies have shown that these cats can still have increased parathyroid hormone concentrations. IRIS provides targets for ideal phosphorus concentrations for each stage of CKD (Table 5). Although it is usually possible to achieve the targets with a kidney diet alone in IRIS stage 2 CKD, by IRIS stage 3 and 4 oral phosphate binders may be needed in addition to diet.

Irrespective of IRIS stage, persistent proteinuria and systemic hypertension should be treated. Proteinuria should always be assessed on at least 2 occasions to document persistence before starting antiproteinuric therapy. IRIS currently recommends that for non-azotaemic cats in IRIS stage 1 CKD, a UP/C >0.4 requires close monitoring and investigation and that cats with UP/C persistently >2.0 should receive antiproteinuric therapy. However, as evidence accumulates, it is likely that the threshold at which treatment is started in non-azotaemic stage 1 cats will fall. For cats with azotaemic stage 2-4 CKD, IRIS recommends starting antiproteinuric medication when UP/C is persistently >0.4.

Proteinuria is most often treated with a combination of controlling systemic hypertension if present, low protein diet, inhibiting the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, omega-3 fatty acids and in some instances, for example if the patient has evidence of protein losing nephropathy (e.g. hypoalbuminaemia), low dose aspirin therapy. The current target recommended by IRIS for control of proteinuria is a UP/C of <0.4.

Measuring blood pressure is important in all geriatric cats, but particularly in those with CKD in order to minimise target organ damage to the eye, kidney, cardiovascular and nervous system. Irrespective of IRIS stage, all cats with hypertensive choroidopathy/retinopathy should start antihypertensive treatment immediately. Cats of all IRIS stages with systolic blood pressure (SBP) measurements persistently (i.e. on at least 2-3 occasions) in the moderate to severe risk categories (SBP >160mmHg; Table 4) should receive antihypertensive treatment.

However, care must be taken, particularly in non-azotaemic cats, to exclude white-coat hypertension. An achievable target for SBP is <160mmHg, i.e. minimal or mild risk of target organ damage. The first line antihypertensive medication in cats is the calcium channel blocker amlodipine besylate (although not a licensed veterinary product), with some cats also requiring additional blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system.

This article was kindly provided by Boehringer Ingelheim, makers of Semintra®:

Full references available on request from Boehringer Ingelheim Limited, Vetmedica Division, Bracknell, Berkshire, RG12 8YS:

* International Renal Interest Society (IRIS): www.iris-kidney.com* International Renal Interest Society (IRIS): www.iris-kidney.com