Canine Benign Prostatic Disease - Part 1

Catriona Curtis BVM&S MRCVS - 12/09/2021

CANINE BENIGN PROSTATIC DISEASE -

Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment (Part 1)

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common ageing process in male entire dogs. It is also a common precursor to other prostatic disease. Whilst one study demonstrated that over 80% of dogs over the age of 5 are affected (O’Shea 1962), some experts believe that 100% of entire male dogs over 8 years have a degree of the condition. It is important to realise that BPH is apparently asymptomatic in a large number of dogs but should be treated to prevent progression and as it is a painful/uncomfortable condition.

Anatomy and Pathogenesis

The canine prostate is a bi-lobed glandular structure in the caudal abdomen. It usually sits within the pelvic canal and encircles the dorsal urethra. It is the only accessory sex gland in the male dog. The role of the canine prostate is still not fully understood. What is known is that it produces prostatic fluid, which helps transport and support sperm during ejaculation (Smith 2008).

BPH develops secondary to the chronic influence of testosterone and its active metabolite, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) on the prostatic cells. It can start to develop as early as 2-3 years of age. It is important to note the importance of DHT in the pathogenesis of the disease. Testosterone is converted to DHT by 5-α reductase in the prostatic epithelia (Kutzler, Yeager 2005).

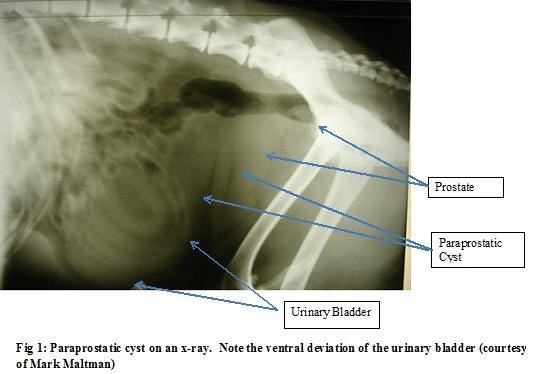

Prostatic cysts often develop secondary to BPH. They can be intra or extraprostatic. Intraprostatic cysts tend to be small and multiple. The size is usually less than 1cm. They are believed to form due to excessive prostatic glandular secretions. Extra-prostatic cysts tend to be retentive cysts and can be as large as 10cm (Smith 2008). The cause is still not fully understood but is believed that squamous metaplasia can be a precursor to development.

Endogenous and exogenous oestrogen is usually the precursor to squamous metaplasia. Common causes can be Sertoli cell tumours or oestrogen administration. As well as being a precursor to cyst formation it can also lead to ductal obstruction or abscessation (Nelson, Couto 2003).

BPH, prostatic cysts and squamous metaplasia can all be precursors for prostatitis – a very common condition which can also be a primary disease. Common causes of bacterial infection can be ascending infection from the lower urinary tract, haematogenous spread, venereal transmission or preputial flora. Isolates often include E.coli, Pseudomonas spp, Klebsiella spp, Pasteurella spp, Staphylococcus spp and Streptococcus spp. Anaerobes are rarely isolated.

Prostatic neoplasia is very rare. It represents less than 1% of diagnosed primary neoplasia in dogs. It is important to note that neutered dogs are over-represented. It appears that testosterone may provide some form of protective effect – the opposite to humans where BPH is often a precursor to prostatic neoplasia. Adenocarcinoma is the most common primary prostatic tumour. Metastasis has often occurred by the time diagnosis has been reached.

BPH

Clinical signs of BPH can include tenesmus, preputial discharge, stranguria, pollakiuria, haematuria, change in faecal size and consistency, stiff hind limb gait and constipation. Often no signs are noted.

The first diagnostic test is usually trans-rectal palpation. The prostate needs to be assessed for size, symmetry, consistency and pain. In some cases the prostate may have dropped over the pelvic brim and may be impossible to palpate. With BPH the prostate should feel bilaterally enlarged, smooth and non-painful.

Odelis CPSE is a relatively new diagnostic test that can be used for prostatic disease. It measures the level of canine prostatic specific serum arginase (CPSE). This enzyme is released by the prostatic epithelia as the level of hyperplasia increases. It is found in blood and sperm. It is a very specific diagnostic test and an excellent indicator of BPH. It can be used in cases where the prostate is not palpable per rectum or as a first line diagnostic test for BPH. Many vets also use it to monitor treatment.

Subsequent tests should include urinalysis; haematuria and proteinuria may be found. If the urine is cultured and is positive then prostatitis needs to be considered as a differential diagnosis. Cytological examination of prostatic washes will often be haemorrhagic with signs of mild inflammation.

Radiography is known to be an insensitive test for BPH or prostatic disease. It can give us information about the approximate size and location of the prostate but that is its limitation.

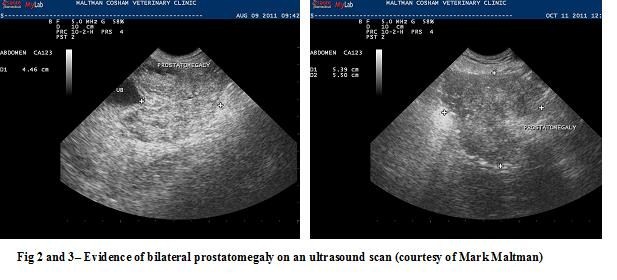

Ultrasonography is much more specific. It is a useful tool to assess the architecture and symmetry of the prostate. With BPH the prostate will be symmetrically enlarged and normoechoic to slightly hyperechoic. Occasionally small fluid filled cysts may be evident.

Prostatic biopsy will provide a definitive diagnosis of BPH. However it is rarely performed if the clinical suspicion is high from the other diagnostic tests and the history.

Treatment of BPH can be surgical or medical. Surgical treatment consists of castration. It is usually a permanent solution. It is not an appropriate option for all dogs though. This may be because of age, concurrent diseases or reluctance by the owner to castrate.

There are two licensed medical treatments for BPH. Delmadinone acetate (Tardak ©) is a progestagen. Adverse effects can include the induction of squamous metaplasia, changes in fertility and suppression of the hypothalamic pituitary axis (HPA). Treatment often needs to be every 3-4 weeks.

Osaterone Acetate (Ypozane ©) is a specific anti-androgen licensed specifically for the treatment of BPH. It has a dual action to competitively prevent the binding of androgens to their prostatic receptors and blocks the transport of testosterone into the prostate. Its onset of action is rapid – 40% reduction in size of prostate in 2 weeks (Tsutui et al 2000)) and lasts for an average of 5-6 months. Safety data shows that when using the licensed dose there is no suppression of the HPA axis and that blood glucose remains normal during treatment. Breeding function is maintained in dogs treated with Ypozane. The dose is 0.25-0.5mg/kg daily for 7 days. The treatment is also often given prior to or shortly after surgical castration to achieve more rapid resolution of signs.

Come back next week for Part 2 covering cysts and neoplasia.

This article was kindly provided by Virbac, makers of Ypozane. Ypozane contains Osaterone acetate for more information contact Virbac Animal Health on 01359 243243, Woopit Business Park, Windmill Avenue, Woolpit, Bury St Edmunds IP30 9UP. This article was first printed in Veterinary Practice Magazine.

References

Albouy M, Sanquer A, Maynard L, Eun HM. Efficacies of osaterone and delmadinone in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in dogs. Veterinary Record (2008) 163, 179-183

Atalan G, Barr FJ, Holt PE. Comparison of ultrasonographic and radiographic measurements of canine prostatic dimensions. VetRadiol Ultrasound 1999;40:408–12.

Bamberg-Thalen BL, Linde-Forsberg C. Treatment of canine benign prostatic hyperplasia with medroxyprogesterone acetate. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1993;29:221–6.

Black GM, Ling GV, Nyland TG, Baker T. Prevalence of prostatic cysts in adult, large-breed dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1998;34:177–80.

Bryan JN, Keeler MR, Henry CJ, Bryan ME, Hahn AW,Caldwell CW. A population study of neutering status as a risk factor for canine prostate cancer. Prostate 2007;67:1174–81.

EMEA. Ypozane scientific discussion.

Evans HE, Christensen GC. The urogenital system. In: Miller’s anatomy of the dog. WB Saunders; 1993. p. 514–516.

Gloyna RE, Siiteri PK, Wilson JD. Dihydrotestosterone in prostatic hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 1970;49:1746–53.

Gobello C. Dopamine agonist, anti-progestins, anti-androgens, long-term-release GnRH agonists and anti-estrogens in canine reproduction: a review. Theriogenology 2006;66:1560–7.

Gobello C, Corrada Y. Noninfectious prostatic diseases in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Vet 2002;24:99–107.

Johnston SD, Root Kustritz MV, Olson PN. Disorders of the canine prostate. In: Canine and feline theriogenology. WB Saunders; 2001. p. 337–355.

Krawiec DR, Heflin D. Study of prostatic disease in dogs: 177 cases (1981–1986). J Am Vet Med Assoc 1992;200:1119–22.

Kutzler M, Yeager A. Prostatic diseases. In: Textbook of veterinary internal medicine. WB Saunders; 2005. p. 1809–1819.

LeRoy BE and Northrup N. Prostate cancer in dogs: Comparative and clinical aspects. The Veterinary Journal 2008; doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2008.07.012

Ling GV, Branam JE, Ruby AL, Johnson DL. Canine prostatic fluid: techniques of collection, quantitative bacterial culture, and interpretation of results. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1983;183:201–6.

Memon MA. Common causes of male dog infertility. Theriogenology 2007;68:322–8.

Nelson RW, Couto CG. Small Animal Internal Medicine – Disorders of the prostate gland; WB Saunders 2003 p.927-932

O'Shea J.D. Studies on the canine prostate gland: Factors influencing its size and weight. J. Comp. Pathol. 1962 72: 321-331.

Parry N. The canine prostate gland Part 1 – non inflammatory diseases. UK Vet Vol 12 No 1 January 2007

Ruel Y, Barthez PY, Mailles A, Begon D. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the prostate in healthy intact dogs. Vet Radiology Ultrasound 1998;39:212–6.

Smith J. Canine prostatic disease: A review of anatomy,pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Theriogenology 70 (2008) 375–383

White RAS. Prostatic surgery in the dog. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2000;15:46–51.

This article was originally published on VetGrad.co.uk in 2013.